Enhancing activity of marijuana-like chemicals in brain may treat Parkinson's Disease

Feb 8, 2007 - 3:28:51 AM

, Reviewed by: Dr. Ankush Vidyarthi

|

|

|

"This study points to a potentially new kind of therapy for Parkinson's disease."

|

|

Key Points of this article

|

|

Endocannabinoids helped trigger a dramatic improvement in mice with a condition similar to Parkinson's.

|

|

However, their findings don't mean smoking marijuana could be therapeutic for Parkinson's disease.

|

|

|

|

By Stanford University Medical Center,

[RxPG]

|

| The study reports that endocannabinoids, naturally occurring chemicals found in the brain that are similar to the active compounds in marijuana and hashish, helped trigger a dramatic improvement in mice with a condition similar to Parkinson's.

|

Marijuana-like chemicals in the brain may point to a treatment for the debilitating condition of Parkinson's disease. In a study to be published in the Feb. 8 issue of Nature, researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine report that endocannabinoids, naturally occurring chemicals found in the brain that are similar to the active compounds in marijuana and hashish, helped trigger a dramatic improvement in mice with a condition similar to Parkinson's.

"This study points to a potentially new kind of therapy for Parkinson's disease," said senior author Robert Malenka, MD, PhD, the Nancy Friend Pritzker Professor in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. "Of course, it is a long, long way to go before this will be tested in humans, but nonetheless, we have identified a new way of potentially manipulating the circuits that are malfunctioning in this disease."

Malenka and postdoctoral scholar Anatol Kreitzer, PhD, the study's lead author, combined a drug already used to treat Parkinson's disease with an experimental compound that can boost the level of endocannabinoids in the brain. When they used the combination in mice with a condition like Parkinson's, the mice went from being frozen in place to moving around freely in 15 minutes. "They were basically normal," Kreitzer said.

But Kreitzer and Malenka cautioned that their findings don't mean smoking marijuana could be therapeutic for Parkinson's disease.

"It turns out the receptors for cannabinoids are all over the brain, but they are not always activated by the naturally occurring endocannabinoids," said Malenka. The treatment used on the mice involves enhancing the activity of the chemicals where they occur naturally in the brain. "That is a really important difference, and it is why we think our manipulation of the chemicals is really different from smoking marijuana."

The researchers began their study by focusing on a region of the brain known as the striatum. They were interested in that region because it has been implicated in a range of brain disorders, including Parkinson's, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and addiction.

The activity of neurons in the striatum relies on the chemical dopamine. A shortage of dopamine in the striatum can lead to Parkinson's disease, in which a person loses the ability to execute smooth motions, progressing to muscle rigidity, tremors and sometimes complete loss of movement. The condition affects 1.5 million Americans, according to the National Parkinson Foundation.

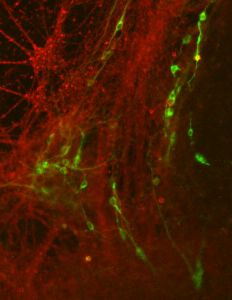

"It turns out that the striatum is much more complicated than imagined," said Malenka. The striatum consists of several different cell types that are virtually indistinguishable under the microscope. To uncover the individual contributions of the cell types, Malenka and Kreitzer used genetically modified mice in which the various cell types were labeled with a fluorescent protein that glows vivid green under a microscope. Having an unequivocal way to identify the cells allowed them to tease apart the functions of the different cell types.

Malenka's lab has long studied how the communication between different neurons is modified by experience and disease. In their examination of two types of mouse striatum cells, Kreitzer and Malenka found that a particular form of adaptation occurs in one cell type but not in the other.

Malenka said this discovery was exciting because no one had determined whether there were functional differences between the various cell types. Their study indicated that the two types of cells formed complementary circuits in the brain.

One of the circuits is thought to be involved in activating motion, while the other is thought to be involved in restraining unwanted movement. "These two circuits are critically involved in a push-pull to select the appropriate movement to perform and to inhibit the other," said Kreitzer.

Dopamine appears to modulate these two circuits in opposite ways. When dopamine is depleted, it is thought that the pathway responsible for inhibiting movement becomes overly activated - leading to the difficulty of initiating motion, the hallmark of Parkinson's disease.

Current treatment for Parkinson's includes drugs that stimulate or mimic dopamine. It turns out that the neurons Kreitzer identified as inhibiting motion had a type of dopamine receptor on them that the other cells didn't. The researchers tested a drug called quinpirole, which mimics dopamine, in mice with a condition similar to human Parkinson's disease, resulting in a small improvement in the mice.

"That was sort of expected," said Malenka. "The cool new finding came when we thought to use drugs that boost the activity of endocannabinoids." Based on prior knowledge of endocannabinoids and dopamine, they speculated that the two chemicals were working in concert to keep the inhibitory pathway in check.

When they added a drug that slows the enzymatic breakdown of endocannabinoids in the brain - URB597, being developed by Kadmus Pharmaceuticals in Irvine, Calif. - the results were striking.

"The dopamine drug alone did a little bit but it wasn't great, and the drug that targeted the enzyme that degrades endocannabinoids basically did nothing alone," Kreitzer said. "But when we gave the two together, the animals really improved dramatically."

Advertise in this space for $10 per month.

Contact us today.

|

|

|

Subscribe to Parkinson's Newsletter

|

|

|

|

About Dr. Ankush Vidyarthi

|

This news story has been reviewed by Dr. Ankush Vidyarthi before its publication on RxPG News website. Dr. Ankush Vidyarthi, MBBS is a senior editor of RxPG News. He is also managing the marketing and public relations for the website. In his capacity as the senior editor, he is responsible for content related to mental health and psychiatry. His areas of special interest are mass-media and psychopathology.

RxPG News is committed to promotion and implementation of Evidence Based Medical Journalism in all channels of mass media including internet.

|

|

Additional information about the news article

|

This work was supported by a Ruth L. Kirchenstein Fellowship, the National Institutes of Health and the National Parkinson Foundation. Neither researcher has financial ties to Kadmus Pharmaceuticals.

Stanford University Medical Center integrates research, medical education and patient care at its three institutions - Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital at Stanford. For more information, please visit the Web site of the medical center's Office of Communication & Public Affairs at http://mednews.stanford.edu.

|

|

Feedback

|

For any corrections of factual information, to contact the editors or to send

any medical news or health news press releases, use

feedback form

|

Top of Page

|