|

From rxpgnews.com Infertility

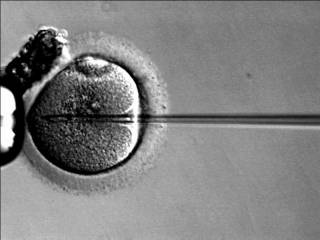

Italian researchers have shown for the first time that it is possible to test a woman's egg, before fertilisation, for chromosomal abnormalities that might make an embryo less likely to implant successfully or more likely to miscarry at a later stage.

"As a consequence, a maximum of three oocytes have to be selected for insemination in order to avoid the development of more than three embryos. However, the three chosen might not be the best oocytes and, especially in women over the age of 35, there is a very high chance of choosing aneuploid oocytes � oocytes where one or two chromosomes have been lost or gained and which, consequently, will develop into embryos that either fail to implant or are more likely to miscarry at a later stage," said Dr Ferraretti, who is scientific director of the Societ� Italiana Studi di Medicina della Riproduzione (SISMER), in Bologna, Italy. Dr Ferraretti and her team decided to see whether analysis of the first polar body could be a safe and effective tool for choosing viable eggs for fertilisation. Previously, no other researcher had attempted to use this technique in "real time" before insemination. "It involves a great team effort and sophisticated technology," said Dr Ferraretti. They performed 510 egg retrievals between March 2004 and July 2005, and in 266 cases they tested the first polar body for five chromosomes among the eight that were known to be most frequently responsible for the aneuploidies detected in miscarriages: chromosomes 13, 16, 18, 21 and 22. The analysis for each retrieval was completed within three hours and a maximum of three apparently normal eggs were inseminated by intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) before being cultured and transferred to the women. In the other 244 cases, the researchers used the conventional criteria of choosing eggs that appeared, on close external inspection, to be normal, before insemination by ICSI. There was little difference in the average number of embryos transferred and the implantation rates between the two groups, but the early miscarriage rate was significantly lower in the group that had had the first polar body (PB1) analysis (11.5% compared to 28.6%). In women aged 34 or younger there was one miscarriage (6%) in the PB1 group compared to seven (21%) in the control group; in women aged between 35 and 37, the PB1 group had two miscarriages (12%) compared to five (50%); and in women aged 38 to 43, there were three miscarriages (18%) in the PB1 group compared to four (33%) in the control group. Dr Ferraretti said: "These preliminary data show for the first time that early PB1 biopsy performed with the aim of having results before insemination does not affect fertilisation, embryo development and implantation potential. The PB1 pre-selection significantly decreased the risk of transferring normally cleaving aneuploid embryos with implantation potential, and therefore decreased the miscarriage rate in all age groups. "At present, because of the limited number of chromosomes that can be analysed, the benefits of the technique are confined to reducing the risk of miscarriages. Therefore, it is indicated for use mainly in women who have a higher risk of aneuploidies because of age, previous miscarriages and repeated IVF failure. "However, in the future, it could become an important tool for all women undergoing assisted reproduction, not just in Italy, but worldwide, and also to reduce the surplus of those frozen embryos that are carriers of aneuploidy." Next, the researchers plan to carry out more tests to check the safety of the procedure, to test different chromosomes that could be responsible for failure in early embryo development or implantation independently from age, and to use the technique to classify and array all the chromosomes in the first polar body. "If and when we are able to have the full information on an oocyte's chromosome competence, assisted reproductive technology will become more efficient. The technique, designed to overcome the most restrictive law regulating infertility treatments, could turn out to be a new predictive tool for assessing the reproductive potential of each patient," she concluded. Other research presented on Monday in 22nd annual conference of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology: ICSI children are developing well at the age of eight A study of 150 of the world's oldest ICSI children has produced reassuring evidence about the health of these children at the age of eight, the 22nd annual conference of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology heard today (Monday 19 June). However, Dr Florence Belva told a news briefing that, in line with previous studies of children conceived using intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), the study showed a slightly higher rate of major congenital malformations. She suggested this could be related to the genetic background of the parents rather than to the ICSI technique. Dr Belva, a paediatrician and research assistant at the Centre for Medical Genetics, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium, said: "Since the introduction of ICSI in 1991 concerns remain about its potential risks for the health and future fertility of offspring. Several studies investigated medical outcome from birth up to the age of five years with reassuring findings. This is the first study to look at the health of ICSI children at the age of eight, just before the onset of puberty." The researchers carried out a detailed physical and neurological examination of 150 ICSI children (76 boys, 74 girls) and compared them with 147 children (76 boys, 71 girls) born without assisted conception. The children were Dutch-speaking, singletons, with at least one European parent, and who were not extremely prematurely born. Dr Belva said: "Major congenital malformations were defined as those causing functional impairment and/or needing surgical correction; all the rest were minor malformations." Examples of major malformations included dextrocardia (where the apex of the heart points to the right instead of the left), large port wine mark (naevus flammeus), groin hernia, squint and problems associated with the ureter (the tube that carries urine from the kidneys to the bladder). Examples of minor malformations included ear abnormalities, mongoloid eyes and overriding toes. "We found no important medical problem in either of the two groups we studied. Weight, height, head circumference and Body Mass Index did not differ between the two groups. Ten per cent of ICSI children (15 out of 150) experienced a major congenital malformation compared to 3.3% (5 out of 147) of the spontaneously conceived (SC) children. Minor malformations were found in 24.1% (35 out of 145) ICSI children compared to 17.2% (25 out of 145) SC children."* The researchers asked another research group in Western Australia to re-assess their data blindly, according to their own coding system. Their results reduced the percentage of major congenital malformations from 10% to 4% amongst the ICSI children, and from 3.3% to 0% amongst the SC children. Minor malformations were reduced from 24.1% to 4.8% in the ICSI children and from 17.2% to 4.8% in the SC children. "Other results showed little, if any, difference between ICSI and SC children, physically or neurologically. ICSI children were not more likely to require additional therapy, to have had surgery or to be hospitalised. There was no greater medication intake or more chronic disease among the ICSI children," said Dr Belva. "Overall, the findings from the clinical examinations at the age of eight are reassuring. There were no clinically important differences between ICSI and SC children. Major congenital malformations appeared to be more frequent in the ICSI group, even after the re-classification exercise; however, most were corrected by minor surgery. "We should remember that malformations occur also in the 'normal' population and can be caused by genetic inheritance, the environment, disease or other causes. If one of the parents has a malformation, they could pass it on to their offspring. We do not think the ICSI technique itself is the cause of the malformations, but is more likely to be related to the parental genetic background and the infertility history of the couple. "The overall general health of eight-year-old singleton ICSI children who were not extremely prematurely born seems satisfactory, but more children should be examined. This is a small study and the children represent the first wave born after the introduction of the ICSI technique in 1991. To include more children of this age, multi-centre studies are necessary. "We are planning long-term follow-up at later milestones in life. We are currently assessing these same children at the age of 10, and we need to check them again later in puberty and afterwards at reproductive age. "The current clinical examinations at this stage of their lives have revealed no major problems; almost all major malformations have been detected by now and there has been no premature onset of puberty. However, from a reproductive and genetic point of view there are some concerns for the future, mainly because of possible fertility problems." How IVF could be causing genetic errors in embryos The conditions in which embryos are cultured in the laboratory during in vitro fertilisation could be causing genetic errors that are associated with certain developmental syndromes and other abnormalities in growth and development, such as low birth weight. Researchers told the 22nd annual conference of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology today (Monday) that preliminary work investigating genetic imprinting in mouse embryos had shown that certain culture media and concentrations of oxygen altered the expression of several imprinted genes. Imprinting is the process by which some genes are activated or inactivated depending on whether they have been inherited in chromosomes from the mother or the father. Professor Paolo F Rinaudo, a scientist at the Center for Reproductive Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, USA, said: "We found that the culture of mouse embryos in the laboratory is sufficient to alter the expression of several imprinted genes and that this effect can be modified by the composition of the culture medium and oxygen concentration. "Interestingly, the expression of one gene, H19, was reduced regardless of the culture conditions, and as H19 is associated with Beckwith Wiedeman syndrome, this finding needs to be investigated further." However, he cautioned against reading too much into his results at this stage. "These studies are important for better directing future resources and studies in humans. But we must remember that these are preliminary results in a mouse model, and they need to be repeated and confirmed in other strains of mice before translating to studies in humans." Other research has suggested that culturing embryos in the laboratory during IVF could be affecting embryos adversely. "Emerging new evidence shows that some neurological and behavioural abnormalities are associated with assisted reproductive techniques. Cases of Angelman and Beckwith Wiedeman syndromes in humans, which are due to aberrant genomic imprinting, and other abnormalities in growth and development in mice have been described after culture in vitro," said Professor Rinaudo. Angelman syndrome is characterised by severe mental retardation, speech impairment, balance disorder and a happy, excitable demeanour; it occurs in about one in 10,000 to 30,000 of the population. Beckwith Wiedeman syndrome is characterised by overgrowth, with an abnormally large tongue, umbilical hernia, neonatal hypoglycaemia and a predisposition to certain tumours, in particular, Wilms tumour and hepatoblastoma; it is rare, occurring in one in 36,000 of the population. Professor Rinaudo and his colleagues cultured mouse embryos in four media with 5% oxygen. Two of the four media were also used with 20% oxygen, making six different cultures in total. As a control, some embryos were left to mature in the mice (in vivo). "We identified 38 imprinted genes, most of which showed no difference in expression after in vitro culture compared to the in vivo embryos. Five genes showed a statistical difference compared to the in vivo control, depending on the culture conditions," he said. The five genes were: * Cd81� expresses a membrane protein with unknown function during embryogenesis. It is involved in T cell development (part of the immune system) and the hepatitis C virus binds to it to gain entry to cells. * H19 � a developmentally regulated gene, thought to be a tumour suppressor and associated with Beckwith Wiedeman syndrome. * Slc38a4 � plays a role in amino acid transport to cells. * Copg2 � plays a role in transport of proteins within cells and is associated with Silver-Russell syndrome, a growth disorder occurring in 1 in 75,000 births (involves intrauterine growth restriction and subsequent poor growth). * Gnas � plays a role in cell signalling and is associated with McCune-Albright syndrome (involves bone, hormone and skin abnormalities), pseudohypoparathyroidism Ib (involves inadequate levels of calcium and excessive levels of phosphates in the blood), and GH-secreting adenomas (type of tumour). Of these, the greatest changes in gene expression were seen in Cd81 (consistently over-expressed in all media) and H19 (consistently under-expressed in all media), but Professor Rinaudo said the significance of these findings was unclear at present. "The next stage of our research is to examine further the effects of IVF and ICSI on the genetic make-up and the form and function of cells from mouse embryos. We want to understand why these techniques appear to be affecting the imprinting of these genes. We hope this understanding will enable the scientific community to make better culture media for IVF in humans." Study links high levels of nitric oxide to infertility and sperm DNA damage Iranian scientists have linked a chemical that plays an essential role in many bodily functions to sperm DNA damage and male infertility, the 22nd annual conference of the European Society of Human Reproduction heard today (Monday). Dr Iraj Amiri, embryology laboratory director at the IVF Centre, Fatemieh Hospital, Hamadan, Iran, said: "In recent years nitric oxide (NO) has been recognised as a molecule that plays an important role in regulating the biology and physiology of the reproductive system, and we know that it can affect human sperm functions, such as motility, viability and metabolism. At low concentrations it can have a positive effect on cells, but a negative effect at high concentrations. "In our study we discovered that there were significantly higher concentrations of nitric oxide in the seminal plasma of infertile patients than in healthy men. High concentrations of NO were significantly correlated with greater sperm DNA damage, and low concentrations of NO were significantly correlated with better sperm motility." The researchers collected semen samples from 45 infertile patients and 70 healthy sperm donors. Most of the infertile men had low sperm counts or poor sperm motility. They measured levels of NO and used a test that can detect DNA damage and repair in individual cells (single cell gel electrophoresis (comet) assay) to determine DNA damage. "We found that the NO levels in the infertile men were, on average, twice as high as in the fertile men," said Dr Amiri. "However, at this stage we were unable to find the cut-off point at which NO levels switched from having a positive effect to having a negative effect. "This study indicates that infertile men have higher levels of sperm DNA damage and NO concentration in their seminal plasma compared to fertile men, and that the sperm DNA damage may be caused by the NO." Dr Amiri said the infertile men may have had higher concentrations of NO because of male genital tract disease and associated factors, such as inflammation and infection, which can lead to NO over-production. There were no significant differences between the fertile and infertile men as to whether they lived in the country or in built-up, traffic-congested areas, although Dr Amiri did not rule out the role played by NO in air pollution. "Our next step is to identify the role of some environmental factors such as air pollution, jobs, disease and smoking on over-production of NO in infertile males. We also want to find a cut-off level at which NO changes from having a beneficial effect on sperm to having a negative affect." New egg freezing technique offers hope to hundreds of women A new and highly successful method of freezing human eggs will help to even out the current inequality between men and women whereby, until now, men have been able to use their previously frozen sperm for IVF treatment but women have not been able to do the same with their eggs. The research, presented today (Monday 19 June) at the 22nd annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, gives hope to hundreds of women who want to preserve their future fertility but who, for whatever reason, only have eggs, not embryos, available for freezing. Dr Masashige Kuwayama told a news briefing that although sperm could be frozen, thawed and used for in vitro fertilisation with high levels of success, the freeze-thawing process could damage eggs and, until now, it had been very difficult to perform successful IVF using frozen-thawed eggs. Research by Professor Stefania Nottola and Dr Sandrine Chamayou, presented at the conference, gave examples of the current problems of conventional freeze-thawing and the need for more effective techniques. It is thought that worldwide less than 150 babies have been born using eggs that have been frozen. Dr Kuwayama, scientific director of the Kato Ladies Clinic in Tokyo, Japan, has developed a new method of freezing eggs (oocytes) called the Cryotop method, which he first used for artificial insemination in sheep and cattle. He said: "The Cryotop method is a highly efficient freezing procedure that opens a new way to resolve the various aspects of the problem of human oocyte cryopreservation. Using this method, we achieved a more than 90% survival rate for the freeze-thawed oocytes and a high pregnancy rate of nearly 42% after the oocytes had been fertilised and implanted in the women. This pregnancy rate is practically the same as the rate we can achieve in our clinic using fresh oocytes." The Cryotop method involves very rapid freezing in a tiny amount (less than 0.1 microlitres) of a special vitrification solution, before storing in liquid nitrogen. This process prevents ice crystals forming, which do so much damage to the structure of the egg. Dr Kuwayama froze 111 eggs, of which 94.5% survived freeze-thawing, 90.5% were fertilised using ICSI (intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection), and 50% of the resulting zygotes were successfully developed for embryo transfer. Twelve pregnancies resulted from 29 embryo transfers (a pregnancy rate of 41.9%, compared with 42.5% using fresh eggs), with an average of 2.3 embryos transferred each time (compared with an average of 1.1 embryos formed from fresh eggs). Eleven healthy babies were born (nine singletons and one pair of twins), while two pregnancies miscarried. The women were aged between 25 and 37. Dr Kuwayama said: "The conventional slow freeze-thawing method has been used successfully for human embryos in assisted reproduction for two decades, but has been far less successful for oocytes. The post-thaw survival rate for human embryos is about 85-90%. Now, using the Cryotop method, we can achieve post-thaw survival rates for oocytes of 90-95%, making oocyte cryopreservation a real option for women. "This technology opens up new horizons for medically assisted reproduction in women, enabling them to have the option of having children at a later date by freezing eggs rather than embryos. Moreover, it will help to eliminate the existing time differences in fertility between men and women, whereby women's supplies of eggs decline at a faster rate than men's supplies of sperm." Dr Chamayou, scientific director of the Unita di Medicina Della Riproduzione, Fondazione HERA, Catania, Italy, told the conference that Italy had banned embryo and zygote freezing in 2004, and any embryos created for IVF, up to a maximum of three, had to be implanted in one transfer. As a consequence of this new law, interest in egg freezing had grown. "Even although oocyte freezing is still considered experimental by the scientific community, nowadays in our centre it is routinely proposed to patients as an alternative to disposing of any surplus oocytes. Surplus oocytes become available in 78.5% of IVF cycles." Her research into the potential of freeze-thawing eggs, using conventional methods of slow freezing and rapid thawing, revealed the consequences of freezing on fertilisation, subsequent initial cell division (cleavage) and embryo quality. Out of 337 thawed eggs, 263 survived (78%), 221 were fertilised using ICSI (67.9%), 116 underwent cleavage up to the second day (77.3%), 92 embryos were implanted in 37 embryo transfer procedures and two pregnancies resulted with two babies born (13.5%, although this figure was not significant due to the small numbers involved). Dr Chamayou also found that the quality of embryos differed significantly depending on whether fresh or frozen eggs had been used; out of the total number of embryos, 36.7% were grade 1 embryos after IVF using fresh eggs, 19.5% were grade 1 after ICSI using fresh eggs (giving an overall percentage after IVF and ICSI of 24.7% grade 1 embryos), but only 12.1% were grade 1 using frozen-thawed eggs. "We concluded that oocyte preservation decreased the proportion of cleavage and grade 1 embryos, but did not influence fertilisation rates," she said. One reason for the high percentage of failure after fertilisation could be the damage done to the structure of the egg during freeze-thawing, in particular to a part called the meiotic spindle which is involved in cell division. The meiotic spindle is a bundle of microtubules, some of which become attached to chromosomes, providing the mechanism for chromosomal movement. "Before freezing we observed meiotic spindles in 62.5% of oocytes, but in only 43.4% after thawing. This is statistically significant and I deduced that cryopreservation may induce irreversible damage to the bonding of the microtubules," she said. Professor Nottola, an associate professor of anatomy in the Department of Anatomy, University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy, told the conference that a variety of abnormalities became apparent when frozen-thawed eggs were inspected more closely, even in those that appeared undamaged after thawing. In addition, the type and/or concentration of agent that was used to protect the egg during freezing (cryoprotectant agent or CPA) might affect the eggs as well. Six eggs were frozen using a multi-step procedure that involved increasing concentrations of ethylene glycol (EG) as a CPA. Twelve were frozen using propane-1,2-diol (PrOH) and two different amounts of sucrose as CPAs. After thawing, the eggs were studied using light and transmission electron microscopy (LM and TEM). The eggs appeared normal when observed with LM, although some eggs showed the development of vacuoles (small cavities that sometimes contain water, food or metabolic waste) in their cytoplasm. When TEM was used, more differences became apparent. These included: * changes to the linkages between mitochondria (microscopic respiratory structures in the cytoplasm) and intracellular membranes amongst the EG-treated eggs * changes to the amount and density of cortical granules (particles that harden the exterior of the egg once it has been fertilised to prevent other sperm penetrating it) * changes to the structure of the egg exterior (the zona pellucida). TEM also confirmed that some eggs, particularly those treated with EG and with the PrOH agent containing more sucrose, had vacuoles developing � a process known as vacuolisation. Professor Nottola said: "These data suggest that frozen-thawed oocytes may look similar to fresh oocytes, but when they are examined more closely it becomes apparent that there are a number of very small but important alterations to specific parts of numerous oocytes, which presumably are responsible for their reduced developmental potential. The type and/or concentration of the CPA used may play a role, at least in part, in producing these alterations. In particular, EG appears less suitable than PrOH. "In my opinion, the most important alteration found in frozen-thawed oocytes could be the presence of vacuolisation. This is a quite non-specific feature commonly found in cells that are responding to an injury and, even in absence of other alterations, might lead to an impairment of the developmental potential of the frozen-thawed oocytes. "As far as the other possible alterations are concerned, the reduction in amount and density of the cortical granules and the consequent hardening of the zona pellucida in frozen-thawed oocytes may be an expected phenomenon that possibly could be by-passed by the application of ICSI technique at insemination; other zona pellucida damage may greatly affect oocyte survival but it depends on the type and amount of the damage; alterations in the mitochondrial organisation can be very subtle and deserve to be further investigated by transmission electron microscopy." Professor Arne Sunde, former chairman of ESHRE, said: "Cryopreservation of human semen and embryos has been a routine procedure since the early 1980s, while cryopreservation of mature oocytes has proved to be very difficult. Current techniques for freezing oocytes have a very low success rates in terms of viable pregnancies per frozen oocyte. This is probably due to basic biological differences between oocytes and sperm cells and embryos. "For decades men have had the opportunity to freeze sperm prior to treatment for malignant diseases, and thousand of babies have been born to couples where the male is an infertile survivor of cancer treatment. With the current techniques, women would need to freeze hundreds of oocytes in order to have a reasonable chance of obtaining a child, but by using the technique of Dr Kuwayama and his colleagues, it will be possible to achieve the same rates of success with 10-20 frozen-thawed oocytes as with fresh oocytes. This is a major improvement, and for the first time, cryopreservation of oocytes represent a realistic option for the preservation of fertility in women who are in need of aggressive treatment for malignant diseases." All rights reserved by www.rxpgnews.com |