Dog Genome Sheds Light on Human Evolution

Dec 8, 2005, 18:38, Reviewed by: Dr. Priya Saxena

|

|

"The incredible physical and behavioral diversity of dogs -- from Chihuahuas to Great Danes � is encoded in their genomes. It can uniquely help us understand embryonic development, neurobiology, human disease and the basis of evolution."

|

By Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard,

An international research team led by scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard announced today the completion of a high-quality genome sequence of the domestic dog, together with a catalogue of 2.5 million specific genetic differences across several dog breeds. Published in the December 8 issue of Nature, the dog research sheds light on both the genetic similarities between dogs and humans and the genetic differences between dog breeds.

Comparison of the dog and human DNA reveals key secrets about the regulation of the master genes that control embryonic development. Comparison among dogs also reveals the structure of genetic variation among breeds, which can now be used to unlock the basis of physical and behavioural differences, as well the genetic underpinnings of diseases common to domestic dogs and their human companions.

"Of the more than 5,500 mammals living today, dogs are arguably the most remarkable," said senior author Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute, professor of biology at MIT and systems biology at Harvard Medical School, and a member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. "The incredible physical and behavioural diversity of dogs -- from Chihuahuas to Great Danes � is encoded in their genomes. It can uniquely help us understand embryonic development, neurobiology, human disease and the basis of evolution."

Dogs not only occupy a special place in human hearts, they also sit at a key branch point in the evolutionary tree relative to humans. By tracking evolution's genetic footprints through the dog, human and mouse genomes, the scientists found that humans share more of their ancestral DNA with dogs than with mice, confirming the utility of dog genetics for understanding human disease.

Most importantly, the comparison revealed the regions of the human genome that are most highly preserved across mammals. "The clustering of regulatory sequences is incredibly interesting," said Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, first author of the Nature paper and co-director of the genome sequencing and analysis program at Broad.

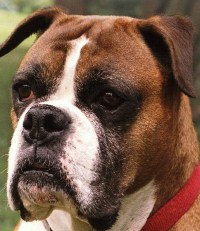

Dogs were domesticated from gray wolves as long as 100,000 years ago, but selective breeding over the past few centuries has made modern dog breeds a testament to biological diversity. Efforts to create the genetic tools needed to map important genes in dogs have gained momentum over the last 15 years, and already include a partial survey of the poodle genome. First, they acquired high-quality DNA sequence from a female boxer named "Tasha," covering nearly 99% of the dog's genome. By comparing these dogs, they pinpointed ~2.5 million individual genetic differences among breeds, called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which serve as recognizable signposts that can be used to locate the genetic contributions to physical and behavioural traits, as well as disease.

Finally, the scientists used the SNP map to reconstruct how intense dog breeding has shaped the genome. They discovered that selective breeding carried large genomic regions of several million bases of DNA into breeds, creating 'haplotype blocks' that are ~100 times larger than seen in the human population. "The huge genomic regions should make it much easier to find the genes responsible for differences in body size, behaviour and disease," said Lander. "Such studies will need many fewer markers than for human studies.

Breeding programs not only selected for desired traits, they also had the unintended consequence of predisposing many dog breeds to genetic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, blindness, cataracts, epilepsy, hip dysplasia and deafness. With the dog genome sequence and the SNP map, scientists around the world now have the tools to identify these disease genes.

|

| Tasha, the boxer from which the DNA for sequencing the dog genome was taken |

"The genetic contributions to many common diseases appear to be easier to uncover in dogs," said Lindblad-Toh. "If so, it is a significant step forward in understanding the roots of genetic disease in both dogs and humans."

For this work, the dog-owner community is an essential collaborator. "We deeply appreciate the generous cooperation of individual dog owners and breeders, breed clubs and veterinary schools in providing blood samples for genetic analysis and disease gene mapping," said Lindblad-Toh.

- Lindblad-Toh, K, et al. (2005). Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature 438, 803-819.

www.broad.mit.edu

Funding and data access

Sequencing of the dog genome began in June 2003, funded in large part by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). The Broad Institute is part of NHGRI's Large-Scale Sequencing Research Network. NHGRI is one of 27 institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The NHGRI Division of Extramural Research supports grants for research and for training and career development at sites nationwide. Information about NHGRI, including the dog genome initiative, can be found at: www.genome.gov.

A complete list of the study's authors and their affiliations:

Kerstin Lindblad-Toh1, Claire M Wade1,2, Tarjei S Mikkelsen1,3, Elinor K Karlsson1,4, David B Jaffe1, Michael Kamal1, Michele Clamp1, Jean L Chang1, Edward J Kulbokas III1 , Michael C Zody1, Evan Mauceli1, Xiaohui Xie1, Matthew Breen5, Robert K Wayne6, Elaine A Ostrander7, Chris P Ponting8, Francis Galibert9, Douglas R Smith10, Pieter J deJong11, Ewen Kirkness12, Pablo Alvarez1, Tara Biagi1, William Brockman1, Jonathan Butler1, Chee-Wye Chin 1, April Cook1, James Cuff1, Mark J Daly 1,2, David DeCaprio1, Sante Gnerre1, Manfred Grabherr1, Manolis Kellis1,13, Michael Kleber1, Carolyne Bardeleben6, Leo Goodstadt8, Andreas Heger8, Christophe Hitte9, Lisa Kim7, Klaus-Peter Koepfli6, Heidi G Parker7, John Pollinger6, Stephen MJ Searle14, Nathan B Sutter7, Rachael Thomas5, Caleb Webber8, Broad Institute Genome Sequencing Platform1, Eric S Lander1,15.

1 Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, 320 Charles Street, Cambridge, MA 02141, USA

2 Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge St, Boston MA 02114, USA

3 Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02141, USA

4 Program in Bioinformatics, Boston University, 44 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

5 Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, 4700 Hillsborough Street, Raleigh, North Carolina 27606

6 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA USA 90095

7 National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, 50 South Drive, MSC 8000, Building 50, Bethesda MD 20892-8000, USA

8 MRC Functional Genetics, University of Oxford, Department of Human Anatomy and Genetics, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QX, UK

9 UMR 6061 Genetique et Developpement, CNRS- Universite de Rennes 1, Faculte de Medecine, 2, Avenue Leon Bernard, 35043 Rennes Cedex, France

10 Agencourt Bioscience Corporation, 500 Cummings Center, Suite 2450, Beverly MA, 01915, USA

11 Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute5700 Martin Luther King Jr Way, Oakland, California 94609, USA

12 The Institute for Genomic Research, Rockville, MD 20850, USA

13 Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Cambridge, MA 02139

14 The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, The Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK

15 Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, 9 Cambridge Center, Cambridge MA 02142, USA

About the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was founded in 2003 to bring the power of genomics to biomedicine. It pursues this mission by empowering creative scientists to construct new and robust tools for genomic medicine, to make them accessible to the global scientific community, and to apply them to the understanding and treatment of disease.

The Institute is a research collaboration that involves faculty, professional staff and students from throughout the MIT and Harvard academic and medical communities. It is jointly governed by the two universities.

Organized around Scientific Programs and Scientific Platforms, the unique structure of the Broad Institute enables scientists to collaborate on transformative projects across many scientific and medical disciplines.

For further information about the Broad Institute, go to http://www.broad.mit.edu.

|

For any corrections of factual information, to contact the editors or to send

any medical news or health news press releases, use

feedback form

Top of Page

|